Making Our History: Artists Render Lincoln’s Legacies

In 2021 and 2022 I co-directed an art residency with UIS Director of Visual Arts Brytton Bjorngaard that was generously funded by the University of Illinois Presidential Initiative: Expanding the Impact of the Arts and Humanities. We worked with twenty Illinois artists to interpret Lincoln’s contemporary legacies. Brytton photographed their art. I wrote short essays to historically contextualize their work. The Storyteller Studios shot videos that showcase the artists’ methods and conceptual approaches. Illinois State University Assistant Professor of Teacher Education Meghan Kessler made accompanying K-12 teacher modules.

Enjoy the show!

K-12 Teacher Modules

The Making Our History art and social science teacher modules use the Inquiry Design Model (IDM) Blueprint and offer teachers great pedagogical flexibility. The modules draw on the photographs, the essays, and the videos.

Teachers can use Cograder, a free AI tool, to modify the readings levels of the essays to any grade level. Just paste the text into Cograder, enter the grade level (e.g., “5” or “fifth”), and press submit. You can convert up to 500 words at a time.

Citations to the essays are available here.

Teachers’ feedback on how they used the modules will help us to improve the modules. To do so, please complete this short questionnaire (MS Word and PDF) and email it to us. Thank you!!

Photos, Essays, and Videos

-

Death haunted Abraham Lincoln from a young age. When he was nine, his mother Nancy died, along with an older married couple who had raised her, and lived with them. All died painfully while he watched. When he was eighteen, his beloved sister Sarah perished in childbirth. At the age of twenty-six, he lost his beau, Ann Rutledge. At the ages of forty and fifty-three, he lost his cherished sons Eddie and Willie. These losses had profound emotional and psychological consequences: both prostrating him in grief and causing him to embrace tenderness and mercy.

But Lincoln’s struggle with death also had a deeply public dimension. By 1860, he led a northern political party—the Republican Party—that proclaimed freedom’s primacy in America. Republicans refused to permit slavery’s expansion. This nationalist reform had been inspired by American abolitionists and generated militant southern protest. During the 1860 campaign, Republicans cavalierly dismissed southern threats of disunion and war. However, the Southerners were not bluffing. They established the Confederate States of America shortly after Lincoln’s election to the presidency and thereafter waged war with determination and perseverance. About 750,000 Union and Confederate soldiers perished during the next four years, and countless others were wounded in mind or body. The calamity was a terrible burden for Lincoln. In 1858 he had told Illinoisans that “I do not expect the Union to be dissolved,” but “I do expect it will cease to be divided.” He expected a peaceful abolition of slavery. By 1862, he knew that his politics had imperiled the Union and helped spur unprecedented bloodletting.

Agonized, he tried to make sense of it. In 1863, at Gettysburg, he urged Americans to dedicate themselves to a new birth of freedom, to a democracy sanctified and elevated by mass death, to an America redeemed, so that “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” His words fashioned a reassuring relationship between reform, death, and democracy. But his invocation of blood sacrifice carried danger because righteousness is often difficult to discern, and, as he well knew, war has few righteous paths. Blood sacrifice is not always redeeming.

America’s war in Vietnam presented just such a case. The country’s leaders meant well in attempting to arrest the spread of communism. Joseph Stalin’s murderous policies in the Soviet Union laid bare communism’s horrors. Protecting the people of South Vietnam from a communist government seemed justified. Moreover, World War I and World War II demonstrated the necessity of interdicting tyranny and building a world safe for democracy. The interests of the Vietnamese and American peoples thus appeared intertwined. But the American intervention on behalf of freedom and democracy did not go as planned. The war for democracy killed over three million Vietnamese and almost sixty thousand Americans. The war’s failure and brutality precipitated an American antiwar protest movement and stimulated other radical reforms. The ingredients of democracy, death, and reform were the same as in the 1860s, but the recipe did not work as well. Few Americans thought the Vietnam war was righteous by the end.

Nathan Peck’s jarring juxtaposition of the 1860s and 1960s highlights the varied and vexing relationship of reform, death, and democracy. By inserting Abraham Lincoln’s face into 1960s photographs, Peck forces us to reconsider the implications of war, pacifism, assassination, and nationalism. Lincoln becomes a grunt, patrolling with a rifle, and relays the message that “War Is Hell.” Lincoln stands in for both John Lennon critiquing the Vietnam War and a civil rights activist marching to Montgomery with Martin Luther King, Jr. Lincoln replaces President Kennedy’s assassin Lee Harvey Oswald, surreally, in a photo of Oswald’s murder by Jack Ruby. And, in a strikingly different image, he becomes an astronaut who helped America reach the moon. In the artworks, reform, death, and democracy in America take different shapes in different instances. Blood sacrifice unites the artworks as a whole, but mostly without redemption. Idealism and progress coexist with tragedy and violence. If art follows life, then the images fittingly portray the bloody histories and uncertain outcomes of both the 1860s and the 1960s.

Nathan Peck Video

Evergreen Park, Illinois

-

Ever since Lincoln’s death, the tension between Lincoln the man and Lincoln the myth has bedeviled anyone who tries to understand his life. Lincoln the man was many things, yet Lincoln the Savior of the Union and Lincoln the Great Emancipator loom largest in the nation’s collective memory. Lincoln wrote many words, yet the most moving and eloquent ones are reproduced like sacred texts in books, cards, websites, films, and museums. Lincoln the man was flesh and blood, but Lincoln the myth is carved into marble. Lincoln the man lived only in a few places, and was not well traveled, yet we see his image everywhere and recognize it instantly: the top hat, the coat, the penny profile, the somber gaze of the Lincoln Memorial. Lincoln the man is gone, but Lincoln the myth lives on amongst us in countless cultural touchstones.

But Lincoln the man did Exist. Grew. Matured. Struggled. Grieved. Loved. Fought. Died. Finding that man requires digging under and around the myth. Sometimes it also requires digging into it.

New Salem is such a case. Lincoln arrived there in 1831 at the age of twenty-two and stayed for six years until leaving to be a fledgling lawyer in Springfield. The years of exploration and growth transformed the young Lincoln. He improved his education, tried many jobs, joined the militia, began a political career, went bankrupt, and made many friends. When he left he was ready to transition from a life of physical toil to a life defined by intellectual power. These were the formative years of Lincoln the man. Ironically, however, much of our knowledge of New Salem stems from reminiscences collected by Lincoln’s law partner William Herndon in the years after Lincoln’s death. New Salem is a place where the man and the myth collide very noticeably.

Ann Rutledge has a special place in the myth. The winsome daughter of a local tavern keeper, Rutledge attracted Lincoln. Her brother later described her as “the brightest mind of the family, was studious, devoted to her duties of whatever character, and possessed a remarkably amiable and lovable disposition.” She had plans to pursue an education, something Lincoln surely admired. Two residents of New Salem who knew him well reported that he courted her for several years, engaged to marry her, and grieved terribly at her death. She was very important to Lincoln the man.

But Ann entered the Lincoln myth in 1866, when Herndon claimed in a public lecture in Springfield that Lincoln loved her to the exclusion of later women, including his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln. This explosive claim embittered Mary and echoed down the decades. In the twentieth century a rising generation of professional historians dismissed Ann’s significance and more generally discredited Herndon’s research. They judged that his carefully collected reminiscences were unreliable, unverifiable, often contradictory, and probably tainted by Lincoln’s remarkable life and tragic death, which made it difficult to trust old stories. Indeed, one historian wrote that Rutledge had become “one of the great myths of American history.” Only in the past thirty years has new scholarship resuscitated the Ann of New Salem, acknowledged her relationship with Lincoln, and reappraised her significance to his life more realistically than did Herndon.

Corey Smith’s virtual reality performance attempts to recover the faint traces of Lincoln in New Salem, particularly Ann’s life and Lincoln’s work as a surveyor. It seeks to find Lincoln the man by situating him in the landscape he once inhabited and surveyed; and it seeks to humanize Ann by resurrecting her memory in the cemetery near New Salem where she is buried. Smith’s art asks us to suspend disbelief, to go beyond myth by entering a virtual world to meet Lincoln and Ann. Virtual reality is a strange form of time travel for historians. But imagination is the only form of time travel for all of us. Perhaps Corey’s performance is a way to find Lincoln the man if we listen and look hard enough. Perhaps it builds his myth.

Corey Smith Video

Chicago, Illinois

-

The selling of Abraham Lincoln began in the 1860 presidential campaign and has not stopped since. In fact, selling him has become an industry. A virtually limitless number of Lincoln items are available for purchase, including souvenir busts, bobble-head dolls, Christmas ornaments, silk ties, socks, reproductions of Civil War photographs, engravings, and historical documents. Aficionados can even purchase the $2,495.00 Krone Abraham Lincoln Gold B NIB Limited Edition Fountain Pen, promoted as the “next best thing to owning a pen used by the former President himself.” Abe is a royalty-free brand that is darn good for business. Americans may reverence Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial, but they purchase Old Abe with abandon everywhere.

Buying a Lincoln Continental is one consequence. Buying an endless supply of Lincoln souvenirs, commemoratives, collectibles, and kitsch is another. Lincoln chia pets, Lincoln pencils, Lincoln logs, Lincoln shirts, and Lincoln hats proliferate ceaselessly, not to mention Lincoln images and Lincoln quotes plastered on everything imaginable that can be sold. The images come in every permutation possible. The quotes are sometimes even correct.

Lincoln objects float on the currents of American culture, whose source is the everlasting dollar. Lincoln was never in favor of beating a dead horse, but beating poor dead Lincoln has proved to be very profitable. Why we buy is a different question. When we purchase Abe, we are buying something beyond the product, some affirmation of Lincoln that matters to us. Perhaps it is a mug that reads “get books, sit down anywhere, and go to reading for yourself.” Perhaps it is a T-shirt that urges “malice toward none; with charity for all.” Perhaps it is a photograph in our home to acknowledge an American leader we admire. In all cases the choice is symbolic and reflects what we value. Lincoln objects typically leverage his elevated character and status as a national icon. As scholar Jackie Hogan has noted, Lincoln’s “name and image imbue diverse causes with qualities like integrity, wisdom, and unimpeachable Americanness.” It seems like an easy sell.

But there is a consequence of selling Lincoln. We get the Lincoln that we buy. Some parts of Lincoln mostly disappear. As a man, and a politician, Lincoln was deep and complex. No one knew this better than his closest companions. Yet very few memorabilia shops are likely to showcase an angry Lincoln, a devious Lincoln, a racist Lincoln, a sexual Lincoln, or a depressed Lincoln. Defaming Lincoln would alienate the customer and perhaps anger the American. Souvenirs, commemoratives, collectibles, and kitsch typically give us an honest Lincoln, an egalitarian Lincoln, a respectable Lincoln, a wise Lincoln, an Olympian Lincoln, and especially a funny Lincoln. A Lincoln we like. The leader who laughed.

Billie Jean Theide illuminates how we learn about Lincoln through objects. Her Perler Bead re-creations of a 4¢ commemorative Lincoln postage stamp and a souvenir Chia Lincoln prod us to contemplate Lincoln in the marketplace. Lincoln would have been delighted with his postage stamp. Congress authorized the first two U.S. postage stamps in 1847, during Lincoln’s two-year term as a congressman: a 5¢ Benjamin Franklin stamp and a 10¢ George Washington stamp. About a century later, on the anniversary of the Gettysburg Address in 1854, he would join those luminaries as post office icons. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a commemorative item distributed by the nation’s postal service, the stamp presents a bearded president who reflects gravitas and leadership: the august Lincoln of legend. The souvenir Chia Lincoln is a different beast entirely, with green Chia sprouts bursting out of Lincoln’s orange clay head. Lincoln’s reaction to his Chia pet is harder to imagine. Perhaps he would have put a stovepipe hat on the green hair after letting out a great guffaw. Or perhaps he would have eaten the hair. Theide’s artworks capture both the serious and the laughing Lincolns and above all our desire to purchase him. The ocean of Lincoln objects tells us little about Lincoln but much about us. We can always find a Lincoln to buy, and usually we can find the Lincoln we want. Sometimes, we find that funny man who saved the nation.

Billie Jean Theide Video

Champaign, Illinois

William Blake

The Lincolns: Hugh Goffinet reenacting a member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade at Fort Stevens

Oil on Linen

-

Between 1936 and 1938 about 3,000 American men joined the Abraham Lincoln Battalion and set off for Spain to fight against fascism. Their mission was to preserve the Spanish Republic from overthrow in civil war. Republicans, socialists, and communists were defending the secular Spanish Republic, established in 1931, while nationalists like General Francisco Franco sought to protect the Catholic Church and to restore the monarchy. Franco began a military coup in 1936 and quickly received military assistance from fascist Italy and Germany. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union recruited anti-fascists from around the world to form an international brigade to sustain the republic. The men of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion served in the XVth International Brigade, fighting bravely until November 1938, when they were demobilized. By that point they had paid a high price for their idealism. Almost seven hundred Americans perished in the effort—and despite this Franco prevailed, and then established a dictatorship in Spain that lasted almost forty years.

The men who joined the Battalion were young but diverse. About seventy percent were in their 20s and another twenty percent were in their 30s. Seamen and students predominated, constituting roughly thirty-eight percent of the volunteers, but the remainder came from a wide-ranging variety of occupations. Four hundred and forty-seven volunteers identified by one historian worked in seventy-four different occupations. Many of them had been active in the union movement during the 1930s. The volunteers skewed heavily towards urban areas. New York, California, Illinois, and Pennsylvania provided about 62% of the volunteers. The remainder came from almost every state in the country. In keeping with Lincoln’s racial doctrines—but not American racial practice—black and white Americans served together in the battalion. A remarkable twenty-five percent of the volunteers were Jewish, to a degree reflecting hostility to Hitler, but also revealing the attractions of the American Communist Party to Jews in the 1930s. Like African-Americans, they were attracted to the communists’ advocacy of both racial and economic equality. The battalion was not a perfect reflection of America’s population, but it was a remarkable mix of idealistic Americans.

What brought the volunteers together was a shared sense of peril and determination. Most were members of the Communist Party, but they were not communist ideologues so much as they were deeply opposed to the rise of right-wing politics in Europe. To them, the Spanish Civil War pitted democracy against fascism. Although not well-versed in the complex politics of Spain, they believed that Spain’s fate augured that of the world more generally. In the words of historian Robert Rosenstone, the “men were joining the struggle of the decade as a reaction to the world around them, the depression, the organization of labor, the threat to their actual or potential freedom posed by the bellicose and expansive fascist powers, which were anti-labor, anti-Semitic, anti-intellectual, and almost anti-civilization.” The volunteers felt compelled to act to avert the coming evil. They sought to save equality and freedom. As poet Edwin Rolfe wrote dismissively of his vacation haunts before volunteering,

This silence is deceptive, the flowers a fraud

the stream polluted. To live here is a lie.

William Blake’s oil painting asks us to perceive the powerful layers of history that shape both art and memory. In Blake’s painting is a man, but what Blake painted is an idea. Hugh Goffinet stares out from the canvas in the dress of a soldier, without being one. He is a reenactor of an African-American volunteer in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. His inspiration is the Lincolns—the battalion’s volunteers—but they are pictured only symbolically, in his dress. Their inspiration was Lincoln, who many decades earlier helped give meaning to the American Civil War, but who is invisible in the painting except by implication—the pose of Hugh Goffinet—which carefully emulates Lincoln’s pose in the celebrated presidential portrait by George Healy. Entirely hidden, at the deepest layer of history, is the true source of inspiration: the human desire for equality and freedom. To understand, honor, and preserve it requires remembrance, in this case with history animating reenactors who animate art that animates memory.

William Blake Video

Lemont, Illinois

-

In 1839, an English playwright coined a felicitous phrase that aptly describes the presidency of Abraham Lincoln:

“Beneath the rule of men entirely great

The pen is mightier than the sword.”

As president, Lincoln used his pen to reach audiences in the northern states, the southern states, and sometimes the world. Doing so required tremendous forethought by a master of the craft. Throughout his three-decade political career he had edited speeches carefully before publication to achieve the best effect for a reading audience. In wartime, he regularly used public letters and published speeches to mold public opinion. He wrote multiple drafts of important documents, refining his language to distill the most skillful phrasing.

In 1863, his public letter to James Conkling in Springfield, Illinois took up the sensitive subject of employing black troops in the Union Army. Many northern Democrats denounced the policy, but Lincoln’s defense of it earned immediate acclaim. He memorably wrote that black soldiers would recall after the war that they helped win it with “silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet,” while some whites would be “unable to forget” that they “strove to hinder” the Union’s victory with “malignant heart, and deceitful speech.” This letter, and others like it, changed hearts and minds. Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the best-selling abolitionist novel, concluded that “the state-papers of no President have more controlled the popular mind.” She could have gone further: only Lincoln’s pen made it possible for the Union Army to continue employing the sword.

At war’s end, however, Lincoln sought to supplant the sword with the pen. The country confronted an array of challenges: reuniting the Union; demobilizing Union and Confederate soldiers; rebuilding the southern economy; and navigating the South’s transition from freedom to slavery, particularly by helping four million newly freed people prosper. Lincoln wanted to win the peace, and he needed public support in the North and South for the unprecedented experiments that lay ahead. Reconciling the country’s people was thus his central object.

In his Second Inaugural Address, Lincoln sought to set the proper tone for reunion. To do so, he acknowledged the North and South’s complicity in the sin of slavery. Agonized by the destruction and violence and bloodshed of the war, Lincoln asked why God had permitted it to continue for so long. He rendered a stark verdict: that God “gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offense came.” This sentence swept aside northern self-righteousness and triumphalism. Urging reconciliation, not recrimination, he called Americans to live in Christian brotherhood. “With malice toward none, with charity for all,” he proposed, “let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle; and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.” Rarely has the pen so eloquently done battle with the sword.

Judith Joseph’s sculpture Pillar of Light illuminates the importance of Lincoln’s pen. The sculpture is Lincoln’s height, crowned by his towering hat. Clustered at the sculpture’s foot are bullets reflecting the terrible wounds of war, and circling above are black birds representing Lincoln’s frequent deep sorrow. Yet the hope that animated his soul and flowed from his pen and moved his countrymen to act is also present. In lieu of his body, his words hang in carved leather strips from his hat to the ground. His body is departed, but his words and example remain to inspire and guide us. Among his most moving words were those in the Second Inaugural, when he urged humility for the victors, mercy for the vanquished, compassion for the bereaved, and peace for the world. Those words, like many others he so carefully crafted, remain a pillar of light for a troubled world still eager for hope.

Judith Joseph Video

Northbrook, Illinois

-

Abraham Lincoln was a man of words. He was much more of course—flesh and blood, calculating and passionate, gloomy and animated, a man, in short—but his words connected him especially powerfully to his contemporaries and have spoken beyond the grave. Lincoln’s life has taken on mythical proportions, but, perhaps surprisingly, behind most of the myths are his remarkable words.

Lincoln was admired during his life for his perseverance in the face of struggle. His resilience was never better exhibited than after his failed attempts in the 1854 and 1858 elections to reach the United States Senate. After the first defeat, he wrote that the “agony is over at last,” but it “is a great consolation” that the Democratic Party was “worse whipped than I am.” He proceeded to build the Illinois Republican Party. After the second defeat, he acknowledged to a correspondent that the election “went hard,” but he expressed “abiding faith” that the Republicans’ antislavery policy will triumph “in the long run.” To bring that triumph to fruition, he exercised his newfound influence in the national Republican Party to help win the 1860 election.

His fortitude stemmed from democratic aspirations. “I am glad I made the late race,” he wrote to a friend in 1858, because “I believe I have made some marks which will tell for the cause of civil liberty long after I am gone.” That cause was universal human freedom and the corresponding right of free men to govern themselves—what Lincoln called “the common right of humanity.” The Civil War tested whether that right could be preserved against an insurgent proslavery government. To Lincoln, the war for the Union was thus a war for humanity. His first annual message to Congress noted that the nation’s population had grown eightfold over seventy years, and its productivity even more. These facts testified to freedom’s current and prospective value to humankind, and thus Lincoln maintained that the “struggle of today, is not altogether for today—it is for a vast future also.”

But whether he aspired equally fervently for the future of all people has been sharply debated. Lincoln famously said in the Lincoln-Douglas debates that “I am not, nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.” He also stated that he saw the nation’s territories “as an outlet for free white people everywhere, the world over—in which Hans and Baptiste and Patrick, and all other men from all the world, may find new homes and better their conditions in life.” This language did not meet the standard of abolitionists at the time—and has been difficult to square with egalitarian sentiments since. Nevertheless, Lincoln’s sentiments in favor of oppressed humanity everywhere frequently blazed forth. The “spirit of our institutions” aims at “the elevation of men,” he wrote in 1859, and “I am opposed to whatever tends to degrade them.”

The two-artist team Industry of the Ordinary visited Springfield, Illinois to search for Lincoln’s mythology in the reflections of common people. They hoped to trace the contours of the Lincoln myth in the minds of Americans. Their artwork, Walking Shadow, wove excerpts from their conversations with ordinary people into an audio recording. One shadow they found was the persevering Lincoln, a man who accomplished remarkable things despite a difficult childhood, a troubled marriage, lost loved ones, and the blood of war. They also discovered Lincoln the aspirational democrat—a man who hated authoritarianism, loved progress, and cared passionately about humanity’s future. A third shadow appeared as the seemingly hesitant emancipator who perhaps valued whites’ interests more than blacks. Doing battle with that shadow was a fourth one, which instead insisted that Lincoln “belongs to everybody.” Artists Adam Brooks and Mathew Wilson did not expect to capture Lincoln’s shadow in full, but what they found has deep roots in Lincoln’s words. His “marks” have indeed struck for liberty “long after” his death. To a remarkable extent, the myth has followed the man.

Industry of the Ordinary Video

Chicago, Illinois

Alexander Martin

Celebration/unfinished business (I(we) am(are) a legacy)

Textiles, Mixed media, performance, and video

-

African-Americans have long had a special relationship with Abraham Lincoln. No matter how highly other Americans may admire Abraham Lincoln, none look to him as their emancipator, whereas most black Americans trace their freedom to the Emancipation Proclamation. When it was issued on January 1, 1863, eleven hundred newly free slaves on the South Carolina Sea Islands, almost all illiterate, requested a white missionary to record their thanks to Lincoln for emancipation. They prayed that God would bless him with “grace, mercy & peace” and expressed hope to meet him “in a better world” because they “never expect to meet your face on earth.” They were among the first black celebrants of Lincoln, but hardly the last. In 1909, eminent black leader Booker T. Washington distinctly recalled his mother kneeling over his body “earnestly praying that Abraham Lincoln might succeed, and that one day she and her boy might be free.” In 1959, the president of Howard University addressed the Michigan legislature on Lincoln’s birthday, “bearing in my heart a deep sense of personal indebtedness to this man, for I am a child of slaves.” African-Americans’ gratitude for Lincoln’s emancipatory role has bubbled up like a wellspring for generations.

They have also long known that they fought for freedom too. Twelve days after Lincoln issued the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, a black newspaperman observed “that the simple stroke of the President’s pen” will not “knock the shackles off of every bondsman.” Instead, the correspondent argued, “the people” needed to cooperate with the president. Soon enough, slaves poured into Union lines and began enrolling in the military. Abolitionist Frederick Douglass proudly declared in August 1863 that they “go into this war to affirm their manhood, to strike for liberty and country.” In 1864, Amos G. Beman added that black abolitionists deserved similar plaudits for having prepared the ground for emancipation during “the past forty years.” Black people never forgot their role in working for freedom, nor did they stop working for full equality and citizenship. As Martin Luther King Jr. justly noted in 1962, the “self-liberation” of slaves who deserted plantations to join the Union army was matched subsequently by the “grim and tortured struggle of Negroes to win their own freedom.” As his life demonstrated, the quest for freedom was unfinished a century later.

African-Americans urging equality in America have drawn on Lincoln to make their case. In 1908, a violent anti-black race riot in Springfield, Illinois—Lincoln’s home—shocked the nation and led to the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. In an influential radio address given on Lincoln’s birthday in 1929, Walter White explained that the NAACP intended “to complete the work of the great emancipator” by achieving “Lincoln’s ideal of justice for all men regardless of color.” White vowed that the NAACP’s fight against injustices harming African-Americans would, like Lincoln’s proclamation, vindicate “the fundamental tenets of the American government.” In 1954, the NAACP proclaimed an auspicious date by which to achieve the equality of African Americans: January 1, 1963. Nobel Peace Prize recipient Ralph Bunche said that Abraham Lincoln would “warmly endorse” a program “to make every American an American in full.” Lincoln had become a powerful talisman in the ongoing fight for black equality.

Alexander Martin’s art and dance bring past and present together to celebrate black freedom and reflect on its contemporary challenges. A painted woman’s shawl depicts the moment of emancipation. Ornamented with nineteenth-century adornments, including lace, a clasp, and a chain, the shawl foregrounds Lincoln on a black background. The black expanse symbolically reflects Lincoln’s aesthetic and his contributions to the freedom of African-Americans. When wearing the shawl and dancing, Alexander embodies the legacy of her ancestors and Abraham Lincoln simultaneously. The dance expresses a joyful, living remnant of African culture and celebrates its persistence in America; it also reflects the unfinished business of freedom. As a human legacy of slavery, Alexander’s dance proclaims her will to persevere and prosper. Abe and her ancestors, together in some better world, warmly endorse it.

alexander Martin Video

Peoria, Illinois

-

One of the remarkable attributes of Abraham Lincoln is the degree to which he rose from humble origins. His family was part of a vast western movement that took European colonists from the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in the early 17th century to the Mississippi River and beyond by the early 19th century. The settlers at the vanguard of that movement lived on the frontier, with relatively little access to markets, goods, information, and education. Life was largely lived within local confines and according to the rhythms of nature, with members of the family working together to provide subsistence. For young men like Lincoln, agricultural labor was not just a norm, but a necessity. Only a small percentage of such men ever graduated from working with their hands to working with their heads.

Lincoln struggled for decades to elevate himself from his humble beginnings. He later wrote that there “was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education” in the “wild region” where “I grew up.” Nevertheless, he learned to read, and did so voraciously when he had the chance. Books opened the door of knowledge that he stepped through on his path to a successful legal and political career. But books alone were not enough. Lincoln tried out many careers before embarking on the law. He worked as a boatman, a storekeeper, a militia man, a postman, and a surveyor, constantly developing new skills with both his hands and his head. What remained constant was his self-reliance, industry, honesty, and perseverance in the face of failure.

Lincoln attributed his success in large measure to his character. Hence he encouraged other men to follow the same path. In 1848, he urged his stepbrother John Johnston, who had asked him for $80 to pay a debt, to “go to work, ‘tooth and nails’ for some body who will give you money.” That same year, he counseled his junior law partner, William Herndon, that the “way for a young man to rise, is to improve himself every way he can, never suspecting that any body wishes to hinder him.” In notes for a law lecture, he advised aspiring attorneys that “diligence” is the “leading rule for the lawyer, as for the man of every other calling.” Behind these attitudes lay a powerful cultural conviction shared by many other nineteenth century Americans: celebration of a man’s right to rise.

Lincoln’s admiration for self-made men deepened his hostility to slavery. He said in 1858 that he had “always hated slavery,” as “much as any Abolitionist.” At the root of his hatred was his recognition of black people’s humanity. Slavery was “cruelly wrong,” he declared, because “the negro is a man.” Correspondingly, black men had the right to rise. Lincoln condemned the theory that a laborer should be “fixed to that condition for life.” Instead, he urged the “prudent, penniless beginner in the world” to labor for wages “a while,” then labor “on his own account another while,” and eventually hire “another new beginner to help him.” Lincoln wanted all men to have the chance to rise from poverty and ignorance, including free blacks and slaves.

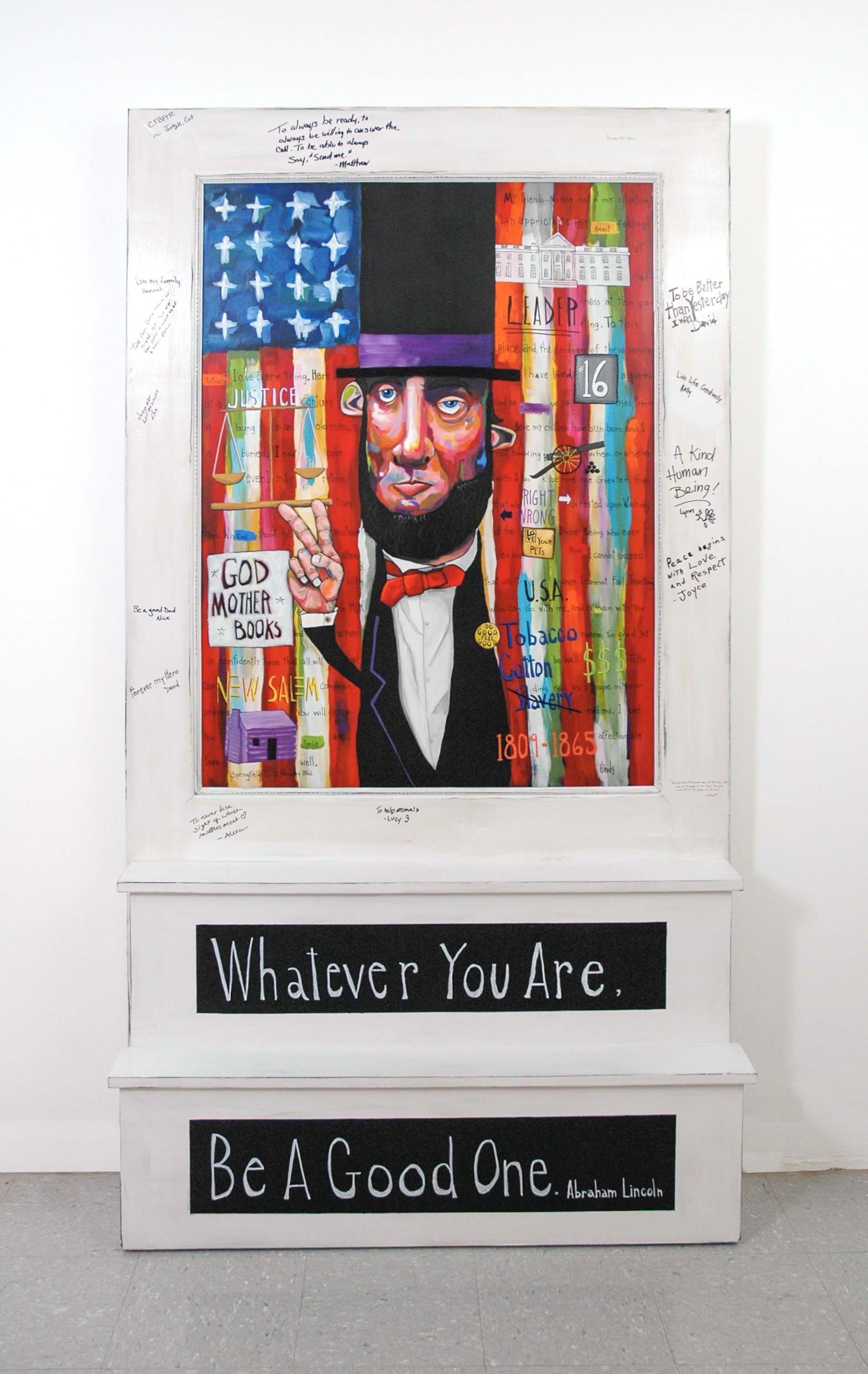

David Hinds encourages us to see this Lincoln in the sculpture Lincoln’s Journey. At the bottom of the sculpture are the words “Whatever You Are, Be A Good One,” which reflect Lincoln’s conviction that individuals should strive to succeed. The sculpture’s painting documents Lincoln’s successful path from New Salem, the frontier village in which he first lived independently, to the White House in Washington DC. The painting’s background—an American flag—signifies American ideals. Words and objects painted on the flag illustrate Lincoln’s journey towards national leadership. Books opened new pathways in his youth and early adulthood, while his mother and stepmother provided guidance. Strength of character shaped his later years. He knew right from wrong, and judged against slavery after weighing it in the scales of justice. As president, his leadership preserved the nation. Abraham Lincoln was indeed “A Good One.”

David Hinds Video

Springfield, Illinois

Don Pollack

chop wood carry water, tale of two cities, A year of living dangerously, war of the world, metamorphosis, & Great expectations

Oil on Canvas mounted on wood panel

-

To painter Don Pollack, the life of Abraham Lincoln encapsulates much of the story of the American Civil War. Lincoln’s life followed a similar arc to that of his country: both began in youthful exuberance on the western frontier and ended in unanticipated calamity—transformed by death into something new. Pollack told this story by painting six evocative book covers, each with a title taken from a classic novel, but each now authored by Abraham Lincoln. The books narrate the intertwined history of the man and the nation.

Abe’s story started in the West. The frontier was the future for the nation and the boy. He grew up on farms in Kentucky, Indiana, and then Illinois. Frontier farming represented opportunity for poor men, but also unrelenting hard labor. To rise from it required a determined effort. In Pollack’s Chop Wood Carry Water, a prairie farm with split rails highlights the backcountry world that represented the nation’s destiny and shaped Lincoln’s character. What the nation would become—and what he would become—was the key question.

Lincoln grew up poor, but free. Most African-Americans grew up enslaved. Frederick Douglass, who later escaped slavery, had no grand hopes of improved circumstances in early life. While young Abe gave speeches on tree stumps and dreamt of becoming a U.S. senator, Douglas just dreamt of being free. In Tale of Two Cities, Pollack captures the tension of a nation divided by slavery—a house divided against itself—a conflict that led Lincoln to leadership of the antislavery Republican Party, Douglass to prominence as the nation’s preeminent black abolitionist, and Southerners to threaten violent resistance to an antislavery federal government.

The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861 precipitated an unparalleled uncertainty in national affairs. Lincoln called the nation to arms, volunteers poured forth, recruits drilled feverishly, anticipation boiled over, and then the war began. Shockingly, the Battle of Bull Run—the war’s first major conflict—ended in a disastrous rout of Union forces. It was the first sign of a terrible, protracted clash. Pollack’s A Year of Living Dangerously highlights the immense risks entailed by Lincoln’s determination to maintain the Union’s perpetuity. Lincoln’s inaugural vow to execute faithfully the laws of the United States meant that he would “not surrender this game,” as he later wrote, “leaving any available card unplayed.”

The Confederates, however, played virtually every card also. The consequence was a modern war of unprecedented violence. Both societies strained every sinew to assemble armies of hundreds of thousands of soldiers, outfitted with deadly rifles and cannon, that repeatedly marched into devastating fire on open fields. The colossal losses that ensued shook each society to the core. In A War of the Worlds, Pollack portrays the deathly pall of the cemetery at Gettysburg, where Lincoln urged Northerners to honor the dead by embracing “increased devotion” to the cause of liberty in America and throughout the globe. The embrace meant another year of carnage.

The United States did not survive the war unchanged. Southern cities rebuilt from rubble, refugees sought new homes, widows remarried, and, when possible, families reunited. Freedpeople explored new lives by wandering roads, searching for relatives, learning to read, and finding new work. Some Americans even tried nobly to bind up the wounds of war, encouraged by a president who advocated mercy and reconciliation instead of recrimination and revenge. Pollack’s Metamorphosis reveals the profound changes experienced by ordinary Americans throughout the land. How the American people would navigate these new changes after the war was the great unknown.

For Lincoln, there would be no life after war. His assassination ended his efforts to knit the country back together. He became a martyr and his task fell to others. Many Republicans desired to remake the South into a civilization invigorated by free labor and enthusiastic freedmen. But powerful currents of resistance from southern whites who dreaded the idea of racial equality dashed these hopes. Pollack’s Great Expectations is an unfinished portrait of Lincoln that copies Gilbert Stuart’s unfinished painting of George Washington. The nation survived Washington’s death, and would survive Lincoln’s. Its future would rest—and still rests—in the hands of the American people.

Don Pollack Video

Evanston, Illinois

Julie Cowan

A Proposition of Equality

Lithography, colored pencil, watercolor, graphite, Swedish tracing paper

-

In one of Abraham Lincoln’s famous undated fragments, he probed the logic of slaveholding. He wrote “You say A. is white, and B. is black. It is color then; the lighter, having the right to enslave the darker? Take care. By this rule, you are to be slave to the first man you meet, with a fairer skin than your own. You do not mean color exactly?---You mean the whites are intellectually the superiors of the blacks, and, therefore have the right to enslave them? Take care again. By this rule, you are to be a slave to the first man you meet, with an intellect superior to your own. But, say you, it is a question of interest; and, if you can make it your interest, you have the right to enslave another. Very well. And if he can make it his interest, he has the right to enslave you.” In eleven taut sentences, Lincoln obliterated three key tenets of the proslavery argument.

Lincoln’s powerful use of logic characterized his entire legal and political career. However, he polished his logical powers by nearly mastering the first six books of Euclid after leaving Congress in 1849. Studying Euclid was not for the faint of heart. It required sustained application by a powerful mind to comprehend Euclid’s use of axioms to deduce mathematical theorems. Lincoln did much of his studying in the middle of the night while on the road traversing central Illinois’ Eighth Judicial Circuit. Often sharing one room with a handful of other lawyers, he ignored their snoring and somehow remained focused on the mathematical proofs.

In the late 1850s Lincoln used Euclidean principles to defend free government. In an important public letter in 1859, he wrote that the “principles of Jefferson are the definitions and axioms of free society.” By this he referred to the idea of human equality, which the Declaration of Independence had called a “self-evident” truth. Equality was the political axiom of the American Revolution: the key assumption from which the revolutionaries had deduced the idea of freedom.

Denying the axiom, however, would bring the entire project down. That denial had begun in earnest with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s Dred Scott decision in 1857, which declared that black men had no rights that white men were bound to respect. In Illinois, Senator Stephen A. Douglas claimed that the founding generation only had referred to white men in the Declaration of Independence. To Lincoln, these claims were the vanguard of “returning despotism,” restoring the principles of “classification, caste, and legitimacy” that justified European monarchies.

In response to Taney in 1857, Lincoln explained the logic of the Declaration of Independence. He observed that “the authors of that notable instrument” did not say that all men were equal in every respect, but they did insist that all were equal in “certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” In doing so, they “meant to set up a standard maxim for free society” that would be “constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated, and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.” Freedom rested on equality. If the axiom of equality prevailed, freedom would follow.

Julie Cowan asks us to consider the importance of Lincoln’s proposition of equality. She overlays Lincoln’s fragment on slavery with a Euclidean diagram, highlighting the importance of Lincoln’s logic in persuading fellow Americans to adopt his ideas about equality and freedom. Below the diagram are typed excerpts of Lincoln’s words--and historians’ reflections on them--that highlight the ideal of equality. Overlaying the excerpts is a phrase that emphasizes Lincoln’s commitment to using logic in the service of persuasion: “Demonstration is the proper goal of argument.” If persuaded by his demonstration, let us put our hands to the wheel; there is much yet to be done to augment “the happiness and value of life to all people of all colors everywhere.”

Julie Cowan Video

Evanston, Illinois

-

Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln’s seamstress, experienced many intimate moments with Abraham Lincoln. She saw him when clothed in political glory and when broken in grief—and movingly described both in her memoir Behind The Scenes. After Lincoln’s assassination, she comforted Mary in the White House and gathered with many of the country’s most illustrious figures around Lincoln’s dead body. “What a noble soul was his,” she wrote, “in all the noble attributes of God!” The moment was reverential. Approaching the body, she recollected, “I lifted the white cloth from the white face of the man that I had worshiped as an idol” and “looked upon as a demi-god.” She considered him the “Moses of my people” and observed that no “common mortal had died.”

Keckley’s recollections of Lincoln’s grandeur as a leader prefigured the attitudes of many black and white Americans in future decades. Black orators heralded the Moses theme annually on January 1 to commemorate emancipation, while other Americans celebrated his role saving the Union. His former secretaries John Hay and John Nicolay especially influenced Lincoln’s image. They spent two decades writing a ten-volume biography that presented the story of a great national hero. Their view shaped the design of the Lincoln Memorial decades later. “He was of the Immortals,” John Hay wrote. “You must not approach too close to the Immortals,” so his “monument should stand alone…isolated, distinguished, and serene.” Keckley had perceived an American demigod in the intimacy of her heart; the memorial carved it in marble for all to see.

But this view did not hold indefinitely. Lincoln’s legacy in the nation’s history eventually came under heightened scrutiny. Probably the most powerful revisionist influence was the 1960s civil rights movement, which spurred historians to study the origins, evolution, and influence of white supremacy. Lincoln did not escape censure. One of the most severe critiques flowed from the pen of journalist Lerone Bennett Jr., who presented Lincoln as an unregenerate racist who favored colonization of freed slaves. Subsequently, scholars increasingly put escaped slaves—not Lincoln—at the heart of emancipation. By running away from their plantations towards Union lines, slaves forced Lincoln to adopt a more radical policy than he desired. By this logic, slaves had “self-emancipated.” Lincoln was no Great Emancipator.

In the summer of 2020, changing historical attitudes came sharply into view. Protests that began in Minneapolis after the murder of George Floyd quickly spread throughout the nation and then the world. In many nations, including the United States and Great Britain, protesters pulled down prominent statues. The statues represented narratives of national purpose and progress that protesters mostly rejected. Suddenly, formerly heroic figures such as Christopher Columbus and Stephen A. Douglas now represented a sordid past of racial oppression. Liberation required reclamation and rededication of public spaces, and thus many statues fell before the rope. Even Abraham Lincoln was not immune. In December 2020, the city of Boston removed a replica of Thomas Ball’s Freedman’s Memorial in Washington DC, which had been funded by freed people commemorating emancipation. In San Francisco, protesters tried to rename Abraham Lincoln High School.

Keenan Dailey’s art is a meditation on Lincoln’s decay as an American god. To Dailey, deifying men serves to promote national ideals and unity, and as time passes the gods powerfully symbolize a nation’s moral purity. The relationship between a national people and its gods therefore usually turns destructive; the gods insulate the nation from criticism and promote patriotic self-righteousness. The consequence is national decay, first of the nation and then of its gods. Dailey’s artworks portray this decay in a video portrait and videogame of Lincoln. The video shows a digital sculpture of Lincoln’s face disintegrating and decomposing over time, interspersed with excerpts from the game environment of a dystopian world where monumental Lincoln carvings remain as remnants of a forgotten past. In each case, democracy has fallen into disrepute and disrepair. Dailey’s art calls for a renewal of American ideals, without the gods, but also testifies to Americans’ changing national attitudes. Elizabeth Keckley would be shocked and dismayed to play the game.

Keenan Dailey video

Champaign, Illinois

-

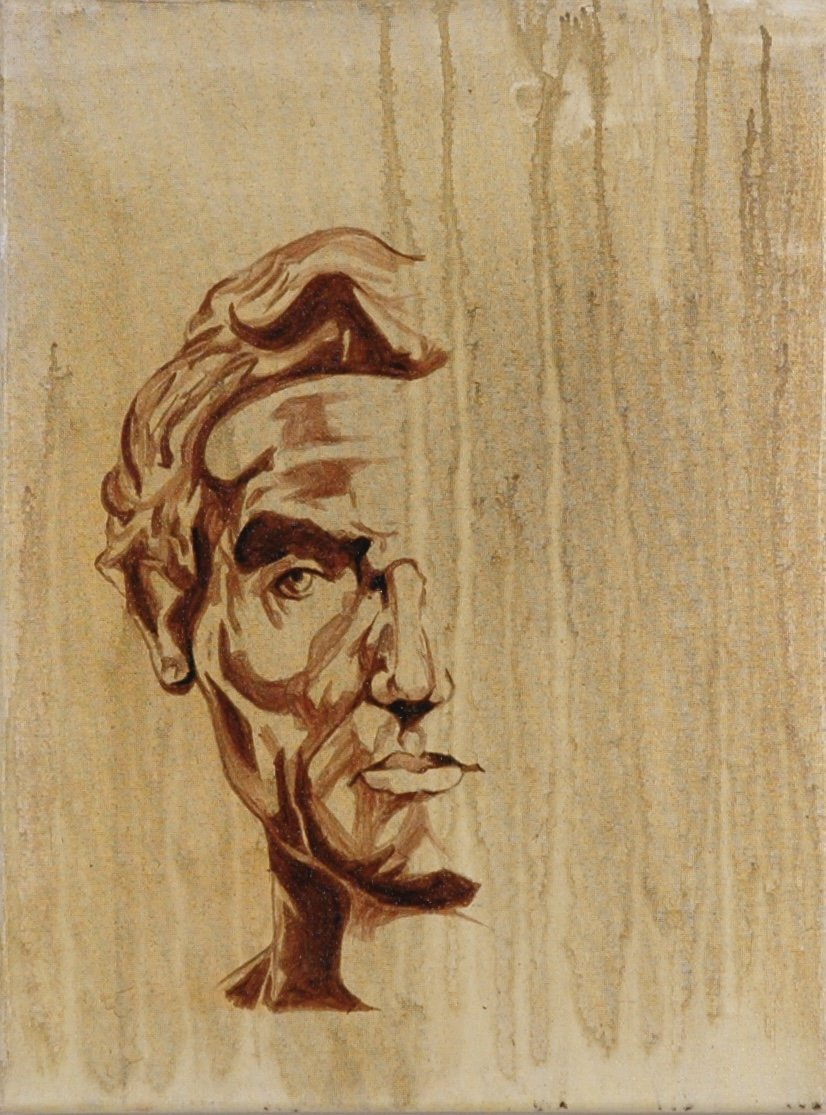

Abraham Lincoln’s face misleads us. It is probably the nation’s most recognizable face, repeatedly photographed and painted during his lifetime, and frequently reproduced since, yet his contemporaries asserted that none of the likenesses captured his true visage. The images were somber, silent, and still, but his living face was animated, expressive, and mobile. As Chicago Tribune reporter Horace White observed, when Lincoln spoke, the “eyes began to sparkle, the mouth to smile, the whole countenance was wreathed in animation.” But only his contemporaries ever saw the smile. Photographic exposures in the 1860s took many seconds, requiring subjects to sit motionless. The laughing Lincoln was never captured on film.

Unmasking the mysteries of the man is no easier than interpreting the stillness of the face. Although a gifted speaker, he was also a man of silences. He kept his own counsel in politics and rarely divulged his most personal concerns to others. David Davis, who traveled and roomed with him for years as a circuit judge, wrote that “he was the most reticent, secretive man I ever saw or expect to see.” Other men who knew him well agreed. William Herndon, his law partner for sixteen years, described him as the most “shut-mouthed” man that ever lived. Lincoln’s bouts with melancholy likely encouraged him to shield his interior life at an early age, and his subsequent careers in politics and law powerfully reinforced the practice of reticence. Both professions required careful stewarding of information. By the 1860s, as one observer noted, his “skill in parrying troublesome questions was wonderful.”

The mythmaking that followed Lincoln’s death makes finding the man especially challenging. The martyred president was immediately hailed as a savior. Countless northern ministers joined Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly in proclaiming that “Christ died to make men holy; he died to make men free.” Republican Party politicians were next to build the myth, using Lincoln’s talismanic power to harvest Republican votes for decades. Meanwhile, a flood of reminiscences poured forth, some shedding light on his life and others altogether fanciful, but most serving to canonize him. Lincoln the man receded farther and farther away.

But we still can glimpse the living man. Doing so requires peering into his intimacy with others. One glimpse comes through his remarkable correspondence about matrimony with his friend Joshua Speed in 1842. Lincoln opened one letter “with intense anxiety and trepidation,” and replied so frankly that he enclosed a decoy letter for Speed to show his wife Fanny if she wanted to read what Lincoln had written. Another glimpse is in Lincoln’s affectionate letter to his wife in 1848 when she asked to join him in Washington DC. “Come on just as soon as you can,” he replied. “I want to see you, and our dear—dear boys very much.” A last glimpse is from Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Todd’s seamstress, who drew a memorable portrait of a dejected President Lincoln collapsing on a couch and shading “his eyes with his hands” due to “dark, dark” war news “everywhere.” But she also recorded him improbably reviving fifteen minutes after picking up the Bible, his “countenance” now “lighted up with new resolution and hope.” She found that he was “reading that divine comforter, Job.” These glimpses bring Lincoln to life.

Printmaker Judith Mayer attempts to recover Lincoln the man in How Will They Remember Me? Cognizant of the many Lincolns in American mythology, she seeks to locate all of them in a human Lincoln, who, like other men, was many things. Among them was a man who slept on pillows. To find that Lincoln, Mayer sewed a white linen pillowcase and printed the name ABE where his head would have rested. She then printed other words over his name to represent the different and sometimes seemingly contradictory Lincolns: Martyr, Papa, Colonizer, Liberator, Target, Savior. Woven into the pillow’s flange edge is Mayer’s ultimate testament to Lincoln’s humanity: unraveled red thread, reflecting the blood on the linen of his deathbed and the poignancy of an unfinished life. Lincoln the man was not martyred, but buried.

Judith Mayer Video

Chicago, Illinois

Jordan Fein

The Melancholy that followed

Acrylic, ink, alcohol based ink, graphite, and colored pencil on canvas

-

Abraham Lincoln played a pioneering role in promoting racial egalitarianism. He was the first president to welcome black visitors to the White House for social visits, political meetings, and public receptions. Black children played with his sons Willie and Tad at the White House, and black visitors repeatedly commented on his hearty welcome and friendly handshake, which surprised and sometimes astonished them. In his first annual message, he asked Congress to support the “novel policy” of acknowledging “the independence and sovereignty of Hayti and Liberia,” and he broached racial barriers by inviting those countries to send black diplomats to Washington DC. He took political advice from black activists like Frederick Douglass, and he was the first president to advocate for black voting rights. After his reelection, African-Americans serenaded him outside the White House. They knew it was their house too.

Lincoln’s assassination therefore hit them like a lightning bolt from a clear sky. Isaac Hill, a black soldier in the Union Army wrote that “No class of people feel his death as the colored people do, for we have lost the best friend we had on our earth, our great deliverer.” Jacob Thomas, a prominent black minister, wrote that “We, as a people, feel more than all others that we are bereaved….He had taught us to love him.” The correspondent for the Anglo-African newspaper in Baltimore reported that “Strong men cried like children, while the women were frantic with sorrow; for in the death of the President they realize the death of a friend—a father." Lincoln was gone. What was to be their fate?

Andrew Johnson, Lincoln’s vice president, proved far more solicitous of white Southerners than of former slaves. He quickly announced amnesty and restoration of property other than slaves to most white Southerners who took an oath of allegiance. He also urged southern states to reenter the Union after making new constitutions that abolished slavery, nullified secession, and repudiated Confederate state debt. In the meantime, southern state legislators passed stringent black codes that profoundly limited the freedoms of African-Americans. Outraged, congressional Republicans refused to seat Southerners elected to Congress, and began battling with President Johnson over the terms of Reconstruction. His disdain for the rights of the freedpeople became clear when he vetoed a civil rights bill passed by Congress. He complained that “the distinction of race and color is by the bill made to operate in favor of the colored and against the white race,” and he insisted that the national government should not interfere with the “municipal legislation” of the states. Johnson did not get his way. The bill was passed over his veto and congressional Republicans took charge of Reconstruction; they passed the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and nurtured biracial Republican Party governments in the southern states. However, the die was cast. Most white Southerners resisted Reconstruction fiercely, and by 1877 Democrats had reasserted control of the southern states. It was not what Lincoln would have hoped.

Jordan Fein mourns Lincoln’s unfinished work. In The Melancholy That Followed, Fein depicts Lincoln’s empty chair at Ford’s Theatre, and surrounds it with symbols of African-American life after Reconstruction. Once white Southerners reclaimed power, the liberties and opportunities of African-Americans constricted rather than expanded. The passage of Jim Crow legislation led to the establishment of whites-only public spaces. Jim Crow laws proved pervasive, potent, and durable, and made black people second-class citizens for much of the next century. Correspondingly, many African-Americans became sharecroppers, a rural proletariat dependent on white landowners and trapped in poverty. Black people also suffered from gross legal injustices, including a chain gang system that put many black prisoners to work for the state. In short, white supremacy combined with greed to sink any prospect of a biracial democracy in the southern states for several generations. Lincoln may not have been able to superintend a more successful Reconstruction—one with a more egalitarian South—but the black people who mourned his assassination probably would have taken their chances. As Jacob Thomas preached to his congregation the day after Lincoln died, “We shall never look upon his like again.”

Jordan Fein Video

Springfield, illinois

-

Mary Todd Lincoln’s life began with promise. Born into the prominent Todd family in Lexington, Kentucky, she received an excellent education. She became fluent in French and deeply interested in politics. In 1836, at the age of eighteen, she moved to Springfield, Illinois in search of a promising spouse. She had numerous suitors, including Lincoln’s political rival Stephen A. Douglas, but she resisted marrying a man she did not love. She wrote to a friend that “my hand will never be given when my heart is not.” She was, however, deeply attracted to a tall Kentuckian named Abraham Lincoln, and gave her hand to him on November 4, 1842. He gave her a ring inscribed “Love Is Eternal.” She predicted that he would become president.

Their life together in Springfield largely brought her dreams to life. She bore four children between 1843 and 1853, and his legal and political careers steadily advanced. They purchased a home and later enlarged it, solidifying their elevated social status. Lincoln was elected to Congress in 1846, pleasing Mary, although his absence pained her. “My Dear Husband,” she wrote, “How much, I wish instead of writing, we were together this evening. I feel very sad away from you.” Both suffered painfully at the death of their son Eddie in 1850, but they responded by having two more children. In 1854, Lincoln’s antislavery political career ignited, and in 1860 he claimed the presidency. For Mary, it was a moment of crowning glory.

But the presidential years were nothing short of nightmarish. His election precipitated secession and civil war. The war proved to be a grinding, deadly contest causing almost unimaginable casualties and tremendous civilian sacrifice and suffering. Both Lincoln and his wife endured withering public attacks, Lincoln for alleged political incompetence and Mary for extravagant spending to refurbish the White House and a penchant for hosting glittering state parties in time of war. Then, in February 1862, their son Willie died of typhoid fever. Mary was inconsolable. She found herself increasingly isolated because Lincoln buried himself in work, overwhelmed with responsibility. Even the joy of winning the war three years later was only a brief reprieve. In the midst of the celebration, on April 14, 1865, the Lincolns visited Ford’s Theatre to watch a play. She was holding Lincoln’s hand when John Wilkes Booth shot him in the head.

Mary lived until 1882, but sadness rather than joy colored most of those years. She had hidden much of her spending from Lincoln and after his death owed thousands of dollars to creditors. Her finances improved in 1870 when Congress approved a pension for her use, but in 1871 death haunted her again, claiming the life of eighteen-year-old Tad Lincoln. Her behavior became more erratic and she increasingly sought to connect with her dead through the aid of spiritualism, mediums, and séances. In 1875, her only remaining son, Robert Todd Lincoln, had her arrested for insanity. Legal struggles with Robert to recover her freedom and property deepened her sadness. Once released, she spent most of her remaining years in France, returning in 1880 to live with her sister in Springfield. Two years later she died of a stroke and rejoined her beloved husband in death, interred under his towering monument in Oak Ridge Cemetery.

Lori Fuller’s drawing of Mary’s sitting table in the White House captures the glory and the heartbreak of her life with Lincoln. She treasured the items portrayed. Her hairbrush, lace, and mirror made possible her elegant appearance; the teacup and dance program reflect her enthusiasm for entertainment and dancing. Her wedding ring and the words “My Dear Husband” show her love for Lincoln, and her pride in his career is shown in a pamphlet of one of his speeches. But the fading roses on the table also testify to the slow fading of her spirit—a consequence of the terrible losses she sustained during and after their marriage. But he was with her to the end, a haunting presence revealed by the ghostly face woven subtly into the grain of the table. They rose, and fell, together.

Lori Fuller Video

Champaign, Illinois

Danny Houk

i will become all one thing or all the other

wood, stain, paint, laser jet print, and acrylic gel

-

One of the most remarkable public performers in the nineteenth century was tightrope walker Charles Blondin. Among his feats was repeatedly crossing the Niagara Falls, which he first traversed in 1859. He crossed it blindfolded, at night, on stilts, walking backwards, pushing a wheelbarrow, and carrying his business manager. Several famous cartoons from the era compared Abraham Lincoln to Blondin. In a cartoon published August 25, 1860, Lincoln carries a slave on his back while balancing himself with a pole titled “Constitution.” The question it asked was whether Lincoln could cross the falls—and preserve the Union—while perilously balancing antislavery politics and American constitutionalism. In another, published September 1, 1864, Lincoln pushes a wheelbarrow containing the nation’s treasures while carrying two Republican members of his cabinet. It questioned whether Lincoln could keep the fractious Republican Party together—and save the nation. He answered, “If my friends will only leave me alone I’m all right.” The cartoons captured Lincoln’s skillful balancing of people, policies, and public opinion during his political career.

The creation of Illinois’ Republican Party owed much to Lincoln’s political skill. Illinois abolitionists desired to launch a new antislavery political party in 1854 after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act enraged many Illinoisans by permitting slaveholders to settle in the new Kansas and Nebraska Territories. However, Lincoln knew that the party could not succeed without antislavery Whigs, Democrats, nativists, and immigrant Germans joining the abolitionists. Whigs and Democrats detested each other, nativists and immigrants distrusted each other, and abolitionists were considered dangerous radicals. Lincoln waited until 1856, when proslavery violence in Kansas Territory further aroused northerners, to coax every group into the Republican Party. To do so, he proposed to return American politics to the founders’ policy on slavery by preventing its spread. While appearing conservative, the policy dovetailed with abolitionist politics and provided much needed common ground. Meanwhile, he pushed nativism to the margins while recruiting nativists to antislavery. The plan worked marvelously, and the same nationalist appeals and deft political touch that enabled coalition building in Illinois became his stepping-stone to the presidency.

Once president, Lincoln’s sagacity enabled him to wage a war for both the Union and emancipation. Abolitionists urged Lincoln early in the war to emancipate slaves, but Lincoln knew that Democratic Party voters and slaveholding Union states would not countenance it. Public opinion had to be prepared for such a revolutionary change in American politics. Biding his time, Lincoln waited until Congress had readied the public for emancipation by confiscating slave property and the war had hardened public sentiment against slaveholders. Lincoln further smoothed the way with a ringing endorsement of Unionism prior to issuing his proclamation: “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and it is not either to save or to destroy slavery.” He then drafted the Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure authorized by the Constitution to preserve the country and invited freed slaves to join the Union’s military. Lincoln’s skillful manipulation of public opinion succeeded. Most northern Democrats denounced emancipation, but from that point forward, Union and emancipation went hand-in-hand, aided by black bayonets.

In sculpting Lincoln’s balancing act, Danny Houk reminds us that both Lincoln and the Union needed stability for survival. Text at the sculpture’s base identifies the fundamental problem both confronted: “I WILL BECOME ALL ONE THING OR ALL THE OTHER.” Slavery divided the Union, and threatened to consume it, while personal and political challenges beset Lincoln and threatened to consume him: frontier deprivation, lifelong depression, the death of two children, the Civil War’s violence, and the Union’s fragility. The sculpture reflects the delicate equilibrium of both man and country by using acrylic gel to impress words and images on irregularly stacked wooden blocks. An ax resting on Lincoln logs reflects his frontier heritage. Toy blocks represent his beloved children, with Eddie Lincoln’s tombstone memorializing their deaths. Maps reveal the Union’s fragility, with cannon and rifle portraying the war’s violence. Building blocks of slaves rest at the sculpture’s base, lifting up the country, but crushed by it. To free them, and save the country, required Lincoln to balance order with reform, to use the power of his pen to sustain and transform the Constitution. Man and country, somehow, balancing together.

Danny Houk Video

Belleville, Illinois

-

Abraham Lincoln was a notoriously permissive father. His youngest sons ran wild in his law office and the White House, scandalizing some visitors. Lincoln even participated in some of their antics. His childhood had been different; his father had required him to labor on the family farm. That approach to parenting made little sense to Abraham and Mary Lincoln. As members of the urban middle class, they nurtured their children and promoted education. They also preferred to build ties of affection with their children through love rather than enforcing obedience through discipline. Lincoln’s parenting was tender, and his assassination in 1865 was a terrible blow for his twelve-year-old son. “I can hardly believe that I shall never see him again,” said Tad. “I must learn to take care of myself now.” Sadly, Tad was not alone. He was one of many bereaved Civil War children.

The Civil War upended the lives of children throughout the country. Tens of thousands of underage boys enlisted in the northern and southern armies, sometimes with the permission of parents, and sometimes not. Many boys served as soldiers. Others served the soldiers, such as drummers, buglers, water carriers, barbers, and couriers. Children who remained at home took up new tasks to replace the lost labor of fathers and brothers at war, whether tending to the farm, cooking, or supervising younger siblings. In the South, hunger regularly stalked children. Additionally, many southerners lost homes or other property to violence, war requisitions, or looting. But the greatest loss for children was the loss of fathers who did not return. In the words of a poem and popular postwar song, they lived with “one vacant chair.”

Black children in contraband camps suffered particularly intensely. About 800,000 African-Americans fleeing slavery found themselves in one of the several hundred refugee camps established by the Union Army. The majority of the inhabitants were children. Conditions in the camps varied, but squalor, exposure to the elements, disease, hunger, and even death were commonplace. Occasional Confederate raids intensified the suffering. Ironically, for camp children, liberation from slavery came mixed with privations, uncertainty, and sometimes fear.

Despite these cruel realities, Booker T. Washington’s life reminds us that freedom created previously unimaginable opportunities for slave children. Washington was born in 1856. He vividly recalled the day of emancipation, when the plantation’s slaves learned “that we were all free, and could go when and where we pleased.” Freedom enabled his mother to unite her children with her husband for the first time. It also enabled Washington to learn to read. His desire to learn knew no bounds. Like the young Abraham Lincoln, he worked during the day and studied at night. One day he heard of a school that educated black people. Determined to attend, he made his way there, virtually penniless, and commenced formal education. His struggle was arduous but transformative, and soon set him on a path to assume leadership of Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. He developed it into a leading institution for African-Americans’ education. He exhorted students to pursue self-improvement through hard work and high character, and spread the doctrine in his influential autobiography Up From Slavery. Washington’s early life was filled with hardship, but his rise shows that emancipating slave children was one of the best legacies of a terrible war.

Lindsay Johnson’s three sculptures of children highlight how the Civil War transformed their lives. In one, Lincoln jauntily carries his son on his shoulders, symbolizing his playful joy in parenthood and the importance of loving bonds between parent and child. In another, a heartbroken girl clutches the Union army cap of her dead father. She evokes the wartime sundering of parental bonds in countless families North and South. In the last, an older boy protectively holds his younger sister as she stares warily into the distance. The children are freed slaves, possibly parentless. What awaited them? Emancipation opened vistas beyond the plantation, but also profound uncertainties. The gift of freedom was the burden of independence: like all other children of the Civil War, black children would walk into an unknown future and find their way.

Lindsay Johnson Video

Oak Park, Illinois

-

Illinois before Lincoln was no haven for black people. The French brought African slaves to the Illinois Country in the early eighteenth century, and after the Revolutionary War American settlers brought additional bondsmen. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 prohibited slavery in the Northwest Territories, but slaveholders held slaves legally as servants by having them sign indentures. Consequently, when Illinois entered the Union as a state in 1818, the state census counted almost 850 slaves and indentured servants, and over 300 free blacks. State laws sharply limited the legal rights of free blacks. To avoid risking arrest, blacks had to register in the locality in which they wanted to live. They could neither testify against whites in court, which made them vulnerable to criminals and kidnappers, nor send their children to public schools. Free blacks protested these laws. In 1822, they petitioned the legislature for suffrage. Having “been rocked in the cradle of liberty and equal rights, taking our ideas of liberty from you,” we “zealously wish” to “participate in that blessing” which would make us “useful citizens” and “enable us to obtain that protection to our persons and property, so well laid down in your constitution and laws, which we are now strangers to.” The legislature instead proposed a constitutional convention to consider whether to legalize slavery in Illinois. Voters defeated the convention movement in 1824, but severely discriminatory black laws stayed on the books until 1865.

Illinoisans were hardly more welcoming to abolitionists than to free blacks. When Illinois abolitionists began organizing in the 1830s, they were regularly shouted down, pelted with objects, or assaulted. On November 7, 1837, the city of Alton became a national byword for anti-abolitionist violence. A drunken mob led by the town’s leading citizens murdered Elijah P. Lovejoy, the antislavery newspaper editor of the Alton Observer. “Two millions and a half of our fellow-creatures are groaning in bondage,” he had written in one characteristic bromide, “crushed to the earth, deprived of rights which their Maker gave them, and which are in themselves inalienable by any conceivable process except that of crime.” Lovejoy’s yoking of evangelical religious convictions to national ideals, and especially to the Declaration of Independence, incensed Alton’s anti-abolitionists, who believed that abolitionism portended disunion and Civil War. Initially they asked Lovejoy to be quiet. Then they strove to quiet him by destroying three of his presses. Finally they murdered him in a blaze of gunfire before breaking up his fourth press and throwing its pieces in the Mississippi River. Lovejoy would never again speak or write about slavery. That task would fall to others.

Building on the work of civil rights reformers and abolitionists, Abraham Lincoln led Illinois’ political movement against inequality and slavery two decades later. In 1854, he declared that “if the Negro is a man, is it not to that extent, a total destruction of self-government, to say that he too shall not govern himself?” In 1858, Lincoln insisted that “each individual is naturally entitled to do as he pleases with himself and the fruit of his labor.” In 1859, he proclaimed that those “who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves.” Crucially, the politics of black activists, Lovejoy, and Lincoln all began with human equality. From that doctrine flowed the Emancipation Proclamation, the Gettysburg Address, and the Reconstruction Amendments that abolished slavery, made black people citizens, and black men voters.

Larsen Husby’s brick sculpture captures Lincoln’s profound leadership in Illinois and the nation. The bricks spell HERE IN LINCOLN LAND. Physically, the bricks are made from clay in Lincoln’s Illinois—a geographic Lincoln Land—whose battles over inequality and slavery spurred an antebellum civil rights and antislavery movement that precipitated Lincoln’s politics. Metaphorically, the sculpture also identifies Lincoln Land—the nation that Lincoln at Gettysburg rededicated “to the proposition that all men are created equal” in “a new birth of freedom.” Lincoln’s language was the political hinge between antebellum reformers who advocated for black equality and postwar Republican Party politicians who pushed for civil rights legislation and the Reconstruction Amendments. Ever since, all Americans live HERE IN LINCOLN LAND.

Larsen Husby Video

Chicago, Illinois

Krista Shelton

The Past, Lincoln battling for Freedom and Justice, & Present/Future

photographic, mixed media, and Digital collage

-

Abolishing slavery was one of Lincoln’s greatest accomplishments as president. The first African landed in Jamestown in 1619, and from thenceforth slavery took root in the British American colonies and then the United States. In the southern colonies, slaves labored to cultivate lucrative cash crops, and after the American Revolution southern state legislators resisted slavery’s abolition. Northern states embraced gradual emancipation during those years, and some southern whites hoped for an antislavery future. However, the development of the cotton gin in 1793 destroyed those dreams. It spurred slavery’s expansion across the southwestern United States over the next half-century. Cotton soon became the economic driver of the southern states and a major engine of the American economy. The slave population quadrupled from approximately one million persons in 1790 to four million in 1860. Growing with it was the horrific interstate slave trade, which moved perhaps as many as a million slaves from the South Atlantic to the southwestern United States between 1820 and 1860. By then slaves constituted the country’s most valuable property other than land.

Uprooting the legal basis of slavery was therefore extremely difficult. For one thing, southern whites had committed themselves to slavery’s perpetuity by the middle of the nineteenth century. They claimed that it was essential for their economic and social well-being. Their attitudes created sharp social and political tensions in the United States. In the North, abolitionists worked industriously for decades to destroy slavery, arguing that it was a great sin. Other antislavery northerners, although more circumspect, also urged national policies favoring freedom. Lincoln was one of them, and in the 1850s rose to political power in Illinois by promoting slavery’s “ultimate extinction.” Although not urging immediate abolition, he did propose federal policy to undermine slavery. However, his election in 1860 did not lead to slavery’s slow demise. Instead, southerners broke up the Union and formed the Confederate States of America to preserve it.

The massive civil war that followed radically altered who had access to political power. The war strained northern resources to the limit and threatened the Union’s survival. The circumstances created an unexpected partnership between Lincoln and the slaves. Lincoln needed slaves to throw off their shackles, join the military, and save the government; the slaves needed Lincoln to emancipate them, admit them into the military, and protect their rights. It was not a perfect partnership, but it was a powerful one, and it was remarkably successful.